Why Most Corporate Culture Initiatives are Flawed

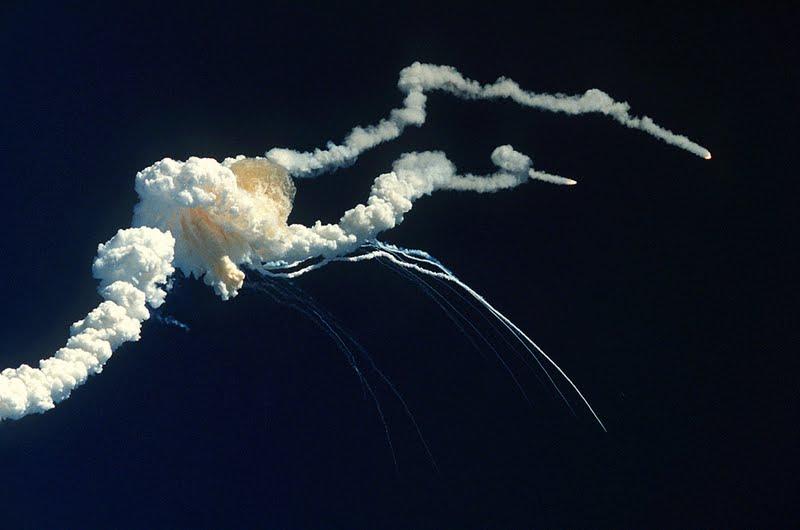

What do the space shuttle Challenger explosion, the BP oil spill, and the Enron energy crisis all have in common? The Normalization of Deviance due to bad corporate culture.

The phrase normalization of deviance was coined by sociologist Diane Vaughan to describe a series of decisions by NASA that lead to the launch of the space shuttle Challenger, despite evidence a launch could be dangerous.

“The gradual process through which unacceptable practice or standards become acceptable. As the deviant behavior is repeated without catastrophic results, it becomes the social norm for the organization.”

Contents

- Why should corporations such as GSK care about culture?

- Corporate Culture has a technical definition.

- Leadership’s perceptions of the culture may be distorted.

- Culture can be measured scientifically.

Context for this Post

GSK has been having culture issues lately. In fact, employee feedback was the only negative metric of GSK Vaccines’ performance last year. Our management has a two-fold plan to address the culture issues.

- Create a focus group to catalyze a small group of employees in the hopes that they will propagate a viral change.

- Author a slide deck with a list of questions to prompt us to think deeper about our behavior and interactions with each other.

I have concerns about both tracts:

The employees chosen for the focus group were almost entirely from the management class.

Management asking everyone to be more introspective is a poorly defined solution to a poorly defined problem.

Why should corporations such as GSK care about culture?

Creating a highly desirable corporate culture provides a sustained competitive advantage; this has been backed by 40 years of research on organizations with rich culture such as Southwest Airlines, Starbucks, and Ritz Carlton (Schein, 1992)1. A cultural assessment is also a key variable in an investigation into a corporation’s development (Leidner & Kayworth, 20062; Schein, 20043; Trefry, 20064).

Poor corporate culture can have disastrous effects. The space shuttle Challenger explosion, the BP oil spill, and the Enron energy crisis all have the normalization of deviance among their root causes. As Price and Williams (2018)5 say, it is only a matter of time before the normalization of deviance causes a major crisis in the health care industry.

Furthermore, GSK executives should be no strangers to the consequences of corporate malfeasance.

Poor corporate culture can also have more subtle negative effects. Employees may not practice desired behaviors if the corporation’s leaders don’t role model the behavior. There could also be low morale due to management decisions conflicting with the espoused corporate values.

Corporate Culture has a technical definition.

As an active area of research, various models have been published with slightly different definitions of what corporate culture is. 6 7 8 9 10 11

| Model | Definition |

|---|---|

| Rossi & O’Higgins (1980) | “Culture is a system of shared cognitions or a system of knowledge and beliefs.” |

| Hofstede (1980) | “The collective programming of the mind which distinguishes members of one human group from another.” |

| Deal & Kennedy (1982) | “The way things get done around here.” |

| Drennan (1992) | “How things are done around here.” |

| House, Wright & Aditya (1997) | “Distinctive normative systems consisting of modal patterns of shared psychological properties among members of collectivities that result in compelling common affective, attitudinal, and behavioral orientations that are transmitted across generations and that differentiate collectivities from each other.” |

| Ogbonna & Lloyd (2002) | “The collective sum of beliefs, values, meanings and assumptions that are shared by a social group and that help to shape the ways in which they respond to each other and to their external environment.” |

A model not mentioned above that is often used in assessments of corporate culture is the Schien (2004)12 three levels model.

Here, corporate culture is the result of physical artifacts and espoused values at the first two levels and a deeper third level that is not visible.

These differing levels are likely the source of the seemingly paradoxical behavior some have observed at many corporations. For example, at the second level GSK may espouse that it values open, honest communication and challenging inappropriate behavior, but may also tacitly admonish such behavior at the third level.

Leadership’s perceptions of the culture may be distorted.

The leadership of a corporation arguably has the greatest responsibility in guiding it’s culture, given their control of resources and ability to decide on corporate initiatives. However, there are several factors that may prevent leaders from perceiving the organizational culture accurately.

Three Circles

In the Three Circles Model of corporate culture, the manager and worker class each experience distinct cultures, with both influenced by the surrounding culture of the country the employees are based in. This is why a focus group tasked with addressing culture issues may not be effective if it is composed almost entirely of the manager class.

Self-Theory

According to self-theory, people have a basic psychological need to maintain a positive self-image, leading to the creation of an idealized self-image (Snyder & Williams, 198213; Sullivan, 198914). Senior leaders in a corporation have often devoted a considerable portion of their career to that corporation, and this may lead to them identifying themselves with the corporation. A possible side effect of this personal investment in the corporation is that senior leaders see criticisms of the corporation as tantamount to criticisms of themselves. This may lead to an inability of the senior leader to perceive negative aspects of the corporation and cause them to dismiss the concerns of others in order to protect the idealized self-image.

Culture can be measured scientifically.

Given the separation between manager and worker culture, and the filters preventing leadership from seeing culture, it is important that corporate culture be measured independently of the leadership. This is typically done using a survey, with the results interpreted using a model that has been validated by statistical factor analysis. One of the most widely used surveys meeting this criteria is the Competing Values Framework (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983)17.

The Competing Values Framework

You can’t have everything.

Once the current culture is identified, the competing values framework is also useful in determining what a corporation wants to do going forward. For example, if GSK wants to be a corporation that is competitive and innovative, that will come at the expense of the bureaucratic control and large, collaborative groups that it currently values.

Review

- Corporate culture is something well worth worrying about,

- because good corporate culture can be a competitive advantage and

- bad culture can have disastrous effects.

- Leadership’s perceptions of the culture may be distorted due to

- the separation of manager and worker cultures (Three Circles model),

- the tendency for committed leaders to see themselves as extensions of the corporation (self-theory), and

- the tendency for committed leaders to see criticisms of the corporation as an attack on their social group (social identity theory).

- Corporate culture has a technical definition and

- Corporate culture can be measured scientifically.

If you believe that the above points are true, then management’s plan to address the culture deficit is seriously flawed. If the problem can be addressed scientifically, why aren’t we? Does GSK want an effective solution to the culture problem?

Schein, E. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.↩

Leidner, D. E., & Kayworth, T. (2006). Review: A review of culture in information systems research: Toward a theory of information technology culture conflict. MIS Quarterly, 30, 357-399.↩

Schein, E. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.↩

Trefry, M. G. (2006). A double-edged sword: Organizational culture in multicultural organizations. International Journal of Management, 23, 563-575.↩

Price MR, Williams TC. When Doing Wrong Feels So Right: Normalization of Deviance. J Patient Saf. 2018 Mar;14(1):1-2.↩

Rossi, Ino and Edwin O’Higgins (1980) ‘The Development of Theories of Culture’, in Ino Rossi (ed.), People in Culture: A Survey of Cultural Anthropology. New York: Praeger.↩

Hofstede, G. (1980). Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 9, 42-58.↩

Deal T. E. and Kennedy, A. A. (1982, 2000) Corporate Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books, 1982; reissue Perseus Books, 2000↩

Drennan, D. (1992). Transforming company culture. London: McGraw-Hill.↩

House, R. J., Wright, N., & Aditya, R. N. (1997). Cross-cultural re- search on organizational leadership: A critical analysis and a pro- posed theory. In P. C. Earley, & M. Erez (Eds.), New perspectives on international/organizational psychology (pp. 535-625). San Francisco: New Lexington.↩

Ogbonna, E., & Lloyd, C. H. (2002). Managing organizational culture: Insights from the hospitality industry. Human Resource Management Journal, 12, 33-53.↩

Schein, E. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.↩

Snyder, R. A., & Williams, R. R. (1982). Self-theory: An integrative theory of work motivation. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 55, 257-267.↩

Sullivan, J. J. (1989). Self theories and employee motivation. Journal of Management, 15, 345-363. ↩

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the or- organization. Academy of Management Review, 14, 20-39.↩

Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63, 224-237.↩

Quinn, R. E. and J. Rohrbaugh. (1983). A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: Towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis. Management Science, 29(3), 363-377.↩

Social Identity Theory

People tend to classify themselves according to the groups they count themselves a member of (Ashforth & Mael, 1989)15, and feel a strong attraction to the group as a whole (Stets & Burke, 2000)16. Consequently, individuals will act on the best interest of the group. While failing to address negative aspects of a corporation may be more harmful in the long run, a possible result of Social Identity Theory is that senior leaders see any criticism of the corporation as an attack on the group.